Juchter van Bergen Quast

Official website of the Family Association of the Barons von Quast

Uitgelicht

Orde van Sint-Mauritius en Sint-Lazarus

De Orde van Sint-Mauritius en Sint-Lazarus werd op 27 december 1816 door Victor Emanuel van Sardinië ingesteld als een Hof- of Adelsorde. De Orde ging terug op de veel oudere, door Amadeus VI van Savoye gestichte Orde van de Verkondiging die onder Emmanuel Philibert II van Savoye in 1572 weer aan de vergetelheid werd ontrukt. In dat jaar werd de Orde met de oude Kruisridderorde, de Orde van Sint-Lazarus, verbonden. Deze Orde bezat rijke commanderijen. Paus Gregorius XIII keurde de fusie in een Pauselijke Bul goed. De Orde had het karakter van een Ridderlijke Orde en de Ridders moesten acht “kwartieren” of adellijke overgrootouders kunnen aantonen. De Orde had een militair en geestelijk, streng katholiek, karakter. In 1816 werd de Orde een moderne Orde van Verdienste. Er waren drie graden en enige karaktertrekken van de oude adelsorde bleven behouden.

De Orde kwam met de Italiaanse monarchie in 1947 ten val maar de afgezette Koning en de pretendenten bleven de Orde als hun huisorde verlenen. De Orde van Sint-Mauritius en Sint-Lazarus is nu een internationaal actieve Ridderlijke Orde en heeft het oude dynastieke karakter niet verloren (Stair Sainty, 2006). Er zijn over de gehele wereld commanderijen die zich voor liefdadigheid en het propageren van de rechtzinnige katholieke leer inzetten (bron: Wikipedia).

R.A.U. Juchter van Bergen Quast is lid van deze Orde.

Literatuur

Guy Stair Sainty en Rafal Heydel-Mankoo, World Orders of Knighthood and Merit, Burke’s Peerage & Gentry (UK) Limited 2006.

Heerlijke rechten

In het werk van C.E.G. ten Houte de Lange, ‘Heerlijkheden in Nederland‘ wordt een heerlijkheid beschreven als: “een conglomeraat van rechten en plichten die betrekking hebben op het bestuur van een bepaald territorium en die in particuliere handen zijn” . Door de hoogleraar A.S. de Blecourt wordt een heerlijkheid in subjectieve zin gedefinieerd als het recht om regeermacht uit te oefenen (aanvankelijk van overheidswege, later door particulieren) met daaraan verknochte heerlijke rechten, krachtens een absoluut vermogensrecht. Heerlijkheid in objectieve zin is het grondgebied, waarbinnen heerlijke rechten kunnen worden uitgeoefend.

Rechtshistorische aspecten

In de nieuwe rechtsorde van 1795, die in Nederland de Bataafse Republiek invoerde, was het instituut van de ambachtsheerlijkheden moeilijk te verenigen met de kreet: Vrijheid, Gelijkheid en Broederschap. De Staatsregeling van 1798 beoogde eens en voorgoed met de heerlijke rechten af te rekenen. De eigenlijke heerlijkheden in institutionele zin schafte zij ineens af. Ook verklaarde zij de gevolgen voor onwettig. Bepaalde rechten werden met name genoemd, doch voor de veiligheid werd alles nogmaals samengevat in een formule, die naar de schijn geen enkel gaatje meer vertoonde: “mitsgaders alle andere regten en verplichtingen, hoe ook genoemd, uit het leenstelsel of leenrecht afkomstig, en die hunnen oorsprong niet hebben uit een wederzijdsch, vrijwillig en wettig verdrag”. Ieder mocht op zijn eigen grond jagen. De honorabele rechten werden afgeschaft zonder enige schadevergoeding. Voor de profitabele moest binnen zes maanden na datum opgave worden gedaan.

In de nieuwe Staatsregelingen van 1801 en 1805 is de grondgedachte van die van 1798 geheel gevolgd. Volgens de regeling van 1801 werd het leenrecht geheel afgeschaft, en alle leenroerige goederen als allodiaal beschouwd. De wet zou aan de leenheren een schadeloosstelling toekennen. Dit laatste is in de Staatsregeling van 1805 nogmaals toegezegd, doch met de uitvoering is nimmer een begin gemaakt. Deze bepalingen leidden er wel toe, dat de Hoge Raad in 1882 besliste, dat de rechten van de ambachtsheren in 1798 niet vervallen waren, doch dat zij mede door de regelingen van 1801 en 1805, van feodaal allodiaal geworden waren. In 1803 bracht de Raad van Binnenlands Bestuur het advies uit, dat een schadevergoeding voor het gemis der “eigenlijk gezegde” rechten (voortkomend uit de jurisdictie) billijk was te achten. Van de andere rechten oordeelde de Raad er vele in strijd met de burgerlijke vrijheid; zij zouden afkoopbaar gesteld moeten worden.

Tot een genuanceerder advies kwamen in 1803 de landsadvocaten in hun rapport aan het Departementaal Bestuur van Holland. Volgens hen bestond er een recht op schadevergoeding, dat trouwens in de wet was vastgelegd. De financiën van de staat lieten die betalingen echter niet toe.

Op 9 juni 1806 herstelde de regering de ambachtsheren in een deel van hun oude rechten. Voordat aan de nieuwe wet uitvoering was gegeven, werd Lodewijk Napoleon koning van Holland. Deze wilde de afschaffing van alle heerlijke rechten tegen een schadevergoeding. Dit ging recht tegen het ontwerp van wet in. De koning droeg de Staatsraad op een nieuw voorstel te formeren. In 1809 is een ontwerp aangeboden, dat in de grote lijn neerkwam op de afschaffing van de jurisdictie en de bevoegdheden, doch de profitabele rechten voor een groot deel wilde handhaven. Aan dit ontwerp onthield Lodewijk Napoleon zijn goedkeuring. Toen in 1810 Holland bij het Keizerrijk werd ingelijfd, besliste de Raad van Ministers het ontwerp tot regeling van de heerlijke rechten aan te houden. De wetten van het Keizerrijk, die sindsdien voor het land van toepassing waren, raakten de vroegere heerlijke rechten nergens direct; alleen voor het recht van aanwas is een Keizerlijk decreet van betekenis geweest. In 1813, toen het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden ontstond, was in feite nog niets veranderd sinds de onduidelijke Staatsregeling van 1798, die een omvangrijke en ingewikkelde materie enkel maar omver gewoeld, doch niet geregeld had.

Actuele status van heerlijke rechten

Van oudsher zijn aan genoemde goederen verbonden zogenoemde eigenlijke heerlijke rechten en heerlijkheidsgevolgen (accrochementen), ook wel oneigenlijke heerlijke rechten genaamd. De eigenlijke heerlijke rechten waren oudtijds de in de handel zijnde rechten op overheidsgezag. Begunstigd door de omstandigheid dat in het oud-vaderlandse recht ten tijde van de Republiek geen scherp onderscheid werd gemaakt tussen privaat- en publiekrecht, hebben deze rechten zich tot de Bataafse omwenteling onverkort weten te handhaven. Bij artikel 24 van de Burgerlijke en Staatkundige Grondregels van de Staatsregeling van 1798 werden zij afgeschaft,¹ doch zestien jaar later bij Souverein Besluit van 26 maart 1814 (Stb. 1814, 46) in getemperde vorm hersteld, namelijk als recht van voordracht voor de vervulling van belangrijke gemeentebedieningen en als recht tot aanstelling in kleinere gemeentebedieningen. Deze rechten werden bij de grondwetsherziening van 1848 afgeschaft ingevolge het eerste lid van het toenmaals ingevoegde additionele artikel. Bij de grondwetsherziening van 1922 werd de werking van deze bepaling uitgebreid tot het kerkelijk collatierecht, dit is het recht iemand in een kerkelijke betrekking voor te dragen of te benoemen. De afschaffing van de in het eerste lid van additioneel artikel I vermelde rechten heeft dus in 1848 respectievelijk 1922 definitief zijn beslag gekregen.

De overige, de zogenaamde oneigenlijke heerlijke rechten, zijn de rechten die de heer kon uitoefenen naast zijn recht op overheidsgezag. Evenals de eigenlijke heerlijke rechten waren dit oudtijds zaken in de handel. De Staatsregeling van 1798 bevatte een drietal bepalingen welke de hier bedoelde rechten limiteerden, namelijk de artikelen 25, 27 en 53 van de Grondregels.²

Tengevolge van de verwarrende redactie van artikel 25 bleef voor tal van rechten grote onzekerheid bestaan. Voor wat betreft een aantal heerlijkheidsgevolgen, bijvoorbeeld het veerrecht, het recht op aanwassen en rechten betreffende dijken en wegen, kan wel als vaststaand worden aangenomen dat zij zijn blijven bestaan. Het eerdergenoemd Souverein Besluit van 26 maart 1814 herstelde onder andere de jacht- en visrechten.

Bij de grondwetsherziening van 1848 werd het niet noodzakelijk geoordeeld de oneigenlijke heerlijke rechten te schrappen, zoals dit met de nog resterende eigenlijke heerlijke rechten geschiedde. De wetgever zou zulks desgewenst later wel kunnen doen. In het tweede lid van het additionele artikel werd dit tot uitdrukking gebracht. Het artikellid maakt tevens gewag van schadeloosstelling der eigenaren.

Sedertdien heeft de wetgever enige regelingen getroffen (de Verenwet (Wet van 5 juli 1921, Stb. 1921, 838), de Jachtwet 1923 (Wet van 2 juli 1923, Stb. 1923, 331) en verschillende opeenvolgende visserijwetten (laatstelijk de Wet van 30 mei 1963, Stb. 1963, 312)). Geheel verdwenen zijn de oneigenlijke heerlijke rechten echter nog niet, al worden zij niet geheel door oud-vaderlands recht beheerst (vgl. HR 20 februari 1931, NJ 1931, blz. 1563, handelend over een heerlijk visrecht). Nog bestaande oneigenlijke heerlijke rechten kunnen in de praktijk worden opgevat als gewone zakelijke rechten (Kamerstukken II 1976-1977, 14 457 (eerste lezing)).

De aard van genoemde rechten staat eraan in de weg dat het kan tenietgaan doordat er het gedurende lange tijd geen gebruik van wordt gemaakt; “non-usus”. De omstandigheid dat het bestaan van de Rechten niet kan afleiden uit de openbare registers, brengt niet mee dat aangenomen moet worden dat de Rechten niet (meer) bestaan (zie onder meer Gerechtshof Amsterdam 23 maart 2010, ECLI:NL:GHAMS:2010:BM9231 en Gerechtshof Amsterdam 2 oktober 2012, ECLI:NL:GHAMS:2012:BY1161).

Naamsgebruik

In Nederland was het gebruikelijk dat de eigenaar van een heerlijkheid de naam daarvan achter zijn geslachtsnaam voegde om aan te geven dat hij de heer was van de betreffende heerlijkheid. Deze toevoeging maakte geen deel uit van zijn wettelijke geslachtsnaam en is te beschouwen als een eigendomsaanduiding. De circulaire die de minister van justitie in 1858 rond liet gaan, dat in officiële stukken een naam van een heerlijkheid nooit als deel van een geslachtsnaam mocht worden opgenomen, werd in de praktijk vaak genegeerd. Aan de ambtenaar van de Burgerlijke Stand werd vaak de naam van de heerlijkheid ten onrechte als deel van de geslachtsnaam opgegeven en vervolgens door de ambtenaar ingeschreven. Aan deze onjuiste opgave kon de betrokkene geen rechten ontlenen. In de praktijk was de kans groot dat in latere akten de onjuiste naam werd overgenomen, net zolang tot een ambtenaar een onderzoek deed naar de naam. Er zijn dus voorbeelden te noemen van geslachtsnamen waaraan de naam van de heerlijkheid is toegevoegd zonder dat er sprake is geweest van een Koninklijk Besluit.

Het stond mensen wel vrij om zich, zolang het geen officiële stukken betrof, te schrijven en ook te noemen met de naam van de heerlijkheid achter de geslachtsnaam.

Bij de invoering van de Burgerlijke Stand in 1811 was het gebruikelijk dat de eigenaar van de heerlijkheid de naam van zijn heerlijkheid achter zijn geslachtsnaam voegde met daartussen het woord van. Kinderen van de heer lieten tussen hun geslachtsnaam en de naam van de heerlijkheid het woord tot zetten.

Tegenwoordig geldt de regel dat iemand die een heerlijkheid alleen bezit, de aanduiding van heer of vrouwe van gevolgd door de naam van de heerlijkheid voert. Als er sprake is van een gemeenschappelijk bezit, noemen de eigenaren zich heer of vrouwe in gevolgd door de naam van de heerlijkheid. Volgens het huidige naamrecht maakt de naam van de heerlijkheid geen deel meer uit van de geslachtsnaam. De aanduiding ‘heer/vrouwe van’ of ‘heer/vrouwe in’ wordt tegenwoordig met een komma gescheiden van de geslachtsnaam. De eigenaar van een huis/landerij hoeft dus niet dezelfde persoon te zijn die de heerlijkheid bezit. Omdat huizen en heerlijkheden vaak dezelfde naam hebben, en omdat de eigenaren zich er vaak naar vernoemden, kan het zijn dat de twee verschillende eigenaren dezelfde naam voeren.

Relatie met de familie

Een voorbeeld van een heerlijkheidsrecht is het collatierecht; naar het Latijn “præsentatio sive collatio”, in het katholiek kerkelijk recht “jus patronatus”. Dit houdt in het recht om een geestelijke, een pastoor of een dominee, voor te dragen ter benoeming. Het recht was erfelijk en werd in Nederland in 1922 afgescha met de bepaling dat de eigenaar het recht tot zijn of haar dood mocht blijven uitoefennen. In een aantal gevallen was het collatierecht verbonden aan een havezate, zoals bij Oosterbroek (zie: Collatierecht – Encyclopedie Drenthe Online), waarvan A.H. van Bergen eigenaar was.

Literatuur

C.E.G. ten Houte de Lange en V.A.M. van der Burg, Heerlijkheden in Nederland, Hilversum, Verloren, 2008.

F.C.J. Ketelaar, Oude zakelijke rechten, vroeger, nu en in de toekomst (Les survivances du ‘système féodal’ dans le droit néerlandais au XIXe et au XXe sciècle) (Leiden/Zwolle 1978).

J.Ph. de Monté ver Loren, ‘Bestaan er nog heerlijkheden en hoe te handelen met aan heerlijkheden ontleende namen?’, De Nederlandsche Leeuw 1961, kol. 394-400.

A. Delahaye, Vossemeer, land van 1000 heren, NV Ambachtsheerlijkheid Oud en Nieuw Vossemeer 1969.

A.S. de Blecourt, Kort begrip van het Oud-Vaderlandsch Burgerlijk Recht I, Groningen-Batavia, 1939, p. 328.

Noten

1. Artikel 24 van de Burgerlijke en Staatkundige Grondregels luidt: “Alle eigenlijk gezegde Heerlijke Regten en Tituls, waardoor aan een bijzonder Persoon of Lichaam zou worden toegekend eenig gezag omtrent het Bestuur van Zaken in eenige Stad, Dorp of Plaats, of de aanstelling van deze of gene Ambtenaaren binnen dezelve, worden, voor zoo verre die niet reeds met de daad zijn afgeschaft, bij de aanneming der Staatsregeling, zonder eenige Schaêvergoeding, voor altijd vernietigd.”

2. Deze artikelen luiden als volgt:

Artikel 25.

-1. Alle Tiend-, Cijns-, of Thijns-, Na-koops-, Afstervings-, en Naastings-Regten, van welken aard, midsgaders alle andere Regten of Verpligtingen, hoe ook genoemd, uit het leenstelsel of Leenrecht afkomstig, en die hunnen oorsprong niet hebben uit een wederzijdsch vrijwillig en wettig verdrag, worden, met alle de gevolgen van dien, als strijdig met der Burgeren gelijkheid en vrijheid, voor altijd vervallen verklaard.

– 2. Het Vertegenwoordigend Lichaam zal, binnen agttien Maanden, na Deszelfs eerste zitting, bepaalen den voet en de wijze van afkoop van alle zoodanige regten en renten, welke als vruchten van wezenlijken eigendom kunnen beschouwd worden. Geene aanspraak op pecunieele vergoeding, uit de vernieting van gemelde Regten voordvloeijende, zal gelden, dan welke, binnen zes Maanden na de aanneming der Staatsregeling, zal zijn ingeleverd.

Artikel 27.

Alle burgers hebben, ten alle tijde, het regt, om, met uitsluiting van anderen, op hunnen eigen of gebruikten, grond te Jagen, te Vogelen en te Visschen. Het Vertegenwoordigend Lichaam maakt, binnen zes Maanden na Deszelfs eerste zitting, bij Reglement, de nodige bepaaling, om, ten dezen opzigte, de openbaare veiligheid en eigendommen der lngezetenen te verzekeren, en zorgt, dat noch de Visscherijen bedorven, noch de Landgebruiker bij eenige Wet of Beding, belet worde, allen Wild op zijnen gebruikten grond te vangen, noch ook, dat een ander daarop zal mogen Jagen of Visschen zonder zijne bewilliging.

Artikel 53.

Bij de aanneming der Staatsregeling, worden vervallen verklaard alle Gilden, Corporatiën of Broederschappen van Neeringen, Ambagten, of Fabrieken. Ook heeft ieder Burger, in welke Plaats woonachtig, het regt zoodanige Fabriek of Trafiek opterigten, of zoodanig eerlijk bedrijf aantevangen, als hij verkiezen zal. Het Vertegenwoordigend Lichaam zorgt, dat de goede orde, het gemak en gerief der Ingezetenen, ten dezen opzigte, worden verzekerd.

Juchter-tweelingen in Riga – Die Rigaer Zwillinge

In de “Kieler Nachrichten” vom 27 januari 1952 wordt verslag gedaan van een bijzondere ontmoeting tussen twee leden van de familie Juchter, te weten Pieter Juchter uit Nederland en Arved Juchter uit Riga. De Nederlandse Juchters komen via Jever uit Edewecht. De Juchters uit Riga komen uit Ostland. De verwandschap moet meer dan 700 jaar terug liggen.

Die Zwillinge von Riga (von Ludwig Finck)

Als Mynheer Pieter Juchter aus Amsterdam, ein Kaufmann, auf seiner ersten Fahrt an die Ostsee in Riga an Land ging, wurde er von einem behäbigen Einwohner begrüßt: “Tag, Herr Juchter!” Er glaubte, sich verhört zu haben und wunderte sich, dass hier jemand seinen Namen wissen sollte, wo er doch völlig unbekannt sein musste. Er begann aber an seinem Verstand zu zweifeln, als er durch die Straßen der Stadt schlenderte und hier und dort den Hut lüften musste, weil er überall freundlich mit “Guten Morgen, Herr Juchter!” angesprochen wurde. “Habe ich eine Visitenkarte an mir?”, fragte er sich, “bin ich durch einen Steckbrief voraussignalisiert worden?”

Als er zum siebenten Male so angegrüßt wurde, stand er still und fragte den Herrn: “Bitte, woher kennen Sie mich?” Der Angesprochene machte ein Gesicht, als sei er nicht ganz bei Trost. “Aber ich werde doch noch Herrn Juchter aus der Grafenstraße kennen. Waren Sie verreist?” “Ich heiße wohl Juchter”, erwiderte Mynheer Pieter, “aber ich bin zum ersten Male in meinem Leben in Riga. Ich wohne in Amsterdam”.

Der Rigaer wollte sich schief lachen. “Sie belieben zu spaßen, Herr Juchter, oder Sie sind Nachtwandler. Sind wir nicht vorige Woche noch im Hotel ’Schwarzer Adler’ zusammengesessen? Haben Sie Ihr Gedächtnis verloren?” “Dann muss ich einen Doppelgänger in Riga haben”, durchfuhr es Pieter. “Wollen Sie mich”, bat er, “nun ja, in meine Wohnung führen?” Und der Einheimische führte ihn und er war starr, als er im Hause Schlossstraße 17 (Pils Straße) zwei Männer sich gegenüber sah, die, wenn auch in verschiedenen Kleidern, ein und dieselbe Person zu sein schienen– Brüder, Zwillinge, selbst aufs höchste betroffen: Arved Juchter aus Riga und Pieter Juchter aus Amsterdam. Sie hatten die gleichen hellblonden Haare, die stahlblauen Augen, die schmale scharfe Nase. Sie konnten einander selber verwechseln.

Ein Gespräch war rasch im Gange, Die Herren hatten sich erst mit Staunen betrachtet wie in einem Spiegel und stellten nun Fragen aneinander, als wären sie vor Jahren auseinander gegangen usw.

Mevrouw Livia Juchter, schoondochter van de Riga-Juchter was getuige van de ontmoeting en schreef later: “Es muss im Jahre 1910 gewesen sein, als die beiden sogenannten Zwillingsbrüder sich kennen lernten. Damals war mein Schwiegervater schon ein alter Herr und Pieter Juchter etwas jünger. Die Schwiegereltern kamen zum Abendbrot mit dem Hollandgast zu uns. Es wurde ein äußerst interessanter und gemütlicher Abend mit Vergleichsanstellungen in Bewegung und Gewohnheiten. Sogar die auffallend gekrümmten kleinen Finger der beiden Herren erregten Verwunderung. Tatsächlich, man konnte nur staunen.”

Bron: Juchter-Juechter: Die Geschichte eines alten Oldenburger Geschlechtes in 6 Abschnitten; Hinrich Tönjes Diedrich Juechter, Hamburg 1959.

Adelslexikon

Tussen 1972 en 2008 verschenen in de reeks Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, die wordt uitgegeven door de Stiftung Deutsches Adelsarchiv, 17 delen van het bekende Adelslexikon. In dit Adelslexikon werden alle “noch blühenden oder nach 1800 erloschenen” Duitse (en Oostenrijkse) adellijke geslachten opgenomen. In 2012 verscheen een 440 pagina’s tellende 18e deel dat geheel bestaat uit een index op de eerdere 17 delen: Adelslexikon Band XVII, Band 151 der Gesamtreihe Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Starke Verlag, Limburg an der Lahn 2012. De index heeft vooral grote waarde omdat het een volledige ontsluiting is op alle samenstellende delen van meervoudige namen. In deel XI (2000) is het onderhavige geslacht Quast opgenomen.

Oudste generaties genealogie Quast

Historici, kunsthistorici en genealogen die onderzoek doen in de periode voorafgaande aan de achttiende eeuw, staan vaak voor grote uitdagingen. Er is veel verdwenen en bijvoorbeeld beeldenstormen, de Reformatie en klimatologische omstandigheden hebben hun sporen nagelaten op de handschriften en objecten die wel bewaard bleven. Verder is er veel verspreid geraakt en daardoor lastig te vinden. Hierdoor is het meestal noodzakelijk om bij oudere generaties een beroep te doen op secundaire bronnen. Hierbij moet worden gedacht aan alle bronnen die niet behoren tot de DTB-registers. Deze bronnen zijn terug te vinden in allerlei archieven, maar de belangrijkste zijn het oud-rechterlijk archief, het oud-administratief archief, het notarieel archief en de rest van de kerkelijke archieven.

De adelsaanspraken van de familie worden onder andere gegrond op een verklaring van het Pruisische Heroldsamt van 5 januari 1892, waarvan de gouverneur van de Nederlandse Antillen een gewaarmerkt afschrift heeft gemaakt op 11 mei 1959. In deze verklaring wordt de adoptie genoemd en een afstamming gegeven. Mevrouw N.C. Römer-Kenepa, destijds hoofd van het Centraal Historisch Archief, heeft in haar brief van 16 september 1996 (kenmerk CHA 9-57) verklaard dat het “afschrift is ondertekend door de Gouverneur drs. A.B. Speekenbrink die in de periode 1957-1961 gouverneur van Curaçao is geweest”.Het door de gouverneur opgestelde afschrift is in de vorm van een notariële akte gedeponeerd op 9 maart 1993 (1) Akte van depot d.d. 11 maart 1997, notaris J.K. Schmitz (voetnoot 38 op p. 376 van Nederlandsche Genealogieen). Mr Juchter van Bergen Quast en Dr A.F. Paula hebben in de archieven van de gouverneur geen verwijzing naar dit afschrift teruggevonden.

De verklaring van het Pruisische Heroldsamt is een secundaire bron. In deze verklaring wordt de oudere genealogie van de familie opgevoerd. De generaties zijn hieronder opgenomen. Hierin wordt ook de aansluiting met de Duitse oeradellijke familie Von Quast gegeven. Het is een onderwerp van onderzoek om voor deze genealogische opstelling nadere ondersteuning te vinden in primaire en andere secundaire bronnen.

I. Kerstien von Quast, auf Garz, tr. N.N.

II. Albrecht von Quast, auf Garz, tr. N.N. von Schlieben.

III. Joachim von Quast, auf Garz, tr. Catharina von Bocholtz, mogelijk dr. van Wilhelm von Bocholtz en Elisa von Hertefeld.

IV. Werner Quast, geb. vóór 10 jan. 1566, leenman van de abdij Gladbach, overl. omstr. 1603.

V. Antonius Quast, geb. Gladbach ± 1570, tr. vóór 3 aug. 1604 Catharina N.N.

VI. Johann Quast, geb. ± 1599, leenman en stadhouder van Odenkirchen, † ald. 26 maart 1654, tr. 1e ± 1623 Odilia Blinten; tr. 2e Wickrathberg 18 febr. 1645 Mergen Kalbs.

Bronnen: verklaring van het Pruisische Heroldsamt van 5 januari 1892; manuscript ‘Stammreihe und Nachkommen der Herren von Quast’.

Onderzoeken C. Goeters

De Duitse genealoog C. Goeters heeft na jaren van onderzoek in de lokale archieven in en rond Düsseldorf de eerdere onderzoeken van Krafft met belangrijk nieuw materiaal heeft aangevuld. De neerslag van het jarenlange intensieve speurwerk van Goeters is gepubliceerd in de Indische Navorscher (1990) met vermelding van de desbetreffende door Goeters ontdekte bronnen (1). Het is Goeters die de stamreeks op basis van authentieke bronnen wist op te voeren tot Werner Quast, leenman van de abdij Gladbach (genoemd onder meer 1566), zijn zoon, Antonius Quast (2) (genoemd 1604), leenman, en kleinzoon Johann Quast (3) (genoemd 1648), aedilis, leenman en stadhouder van Odenkirchen. Deze bewezen stamreeks is ook in het Duitse adelsboek vermeld.

De Duitse genealoog C. Goeters heeft na jaren van onderzoek in de lokale archieven in en rond Düsseldorf de eerdere onderzoeken van Krafft met belangrijk nieuw materiaal heeft aangevuld. De neerslag van het jarenlange intensieve speurwerk van Goeters is gepubliceerd in de Indische Navorscher (1990) met vermelding van de desbetreffende door Goeters ontdekte bronnen (1). Het is Goeters die de stamreeks op basis van authentieke bronnen wist op te voeren tot Werner Quast, leenman van de abdij Gladbach (genoemd onder meer 1566), zijn zoon, Antonius Quast (2) (genoemd 1604), leenman, en kleinzoon Johann Quast (3) (genoemd 1648), aedilis, leenman en stadhouder van Odenkirchen. Deze bewezen stamreeks is ook in het Duitse adelsboek vermeld.

Relatie met het oer-adellijke geslacht Quast

Met brief van 24 augustus 1998 is de verwantschap tussen de in het Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Adelslexikon XI (2000) beschreven tak Quast (de onderhavige tak) en de in het Gothaisches Genealogisches Taschenbuch der Adeligen Häuser (1904) behandelde Duitse tak Quast bevestigd door de chef de famille van de Duitse tak, Sigismund von Quast. De verwantschap is tijdens de op 29-30 september 1998 te Iphofen gehouden familiedag door hem bekend gemaakt.

Familiepapieren: Brieven Sigismund von Quast

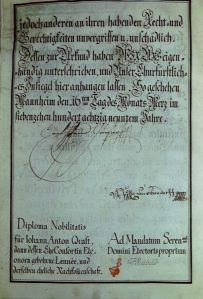

Aspecten van de verheffing in de Rijksadelsstand

In het adelsdiploma van de familie Quast wordt gesproken van een verheffing (Standeserhöhung). De conclusie mag niet getrokken worden dat de familie daaraan voorafgaand niet tot de adel werd gerekend. Bij bestudering van het werk van Freiherr von Freulichstahl ( Georg Freiherr v. Frölichsthal: Nobilitierungen im Heiligen Römischen Reich. Ein Überblick, in: Sigismund Freiherr v. Elverfeldt-Ulm (Hg.): Adelsrecht, Limburg an der Lahn 2001, 67ff), wordt duidelijk dat in het Heilige Roomse Rijk der Duitse Natie talloze, van elkaar verschillende, adelstatuten bestonden. Erkenning hiervan over en weer was allerminst vanzelfsprekend (Frölichsthal, § 2.1.3.3):

In het adelsdiploma van de familie Quast wordt gesproken van een verheffing (Standeserhöhung). De conclusie mag niet getrokken worden dat de familie daaraan voorafgaand niet tot de adel werd gerekend. Bij bestudering van het werk van Freiherr von Freulichstahl ( Georg Freiherr v. Frölichsthal: Nobilitierungen im Heiligen Römischen Reich. Ein Überblick, in: Sigismund Freiherr v. Elverfeldt-Ulm (Hg.): Adelsrecht, Limburg an der Lahn 2001, 67ff), wordt duidelijk dat in het Heilige Roomse Rijk der Duitse Natie talloze, van elkaar verschillende, adelstatuten bestonden. Erkenning hiervan over en weer was allerminst vanzelfsprekend (Frölichsthal, § 2.1.3.3):

Wie dargestellt war das Standeserhöhungsrecht 1467 zu einem Reservatrecht des Kaisers geworden. Die in den Wahlkapitulationen ab 1636 entwickelten Vorbehalte bezüglich einer landesherrlichen Jurisdiktion (vgl. unter 2.1.1.) führten dann in den größeren Territorien recht rasch zu landesherrlichen Ausschreibungen (Anerkennungen, Bestätigungen, Intimationen, Nostrifizierungen); jeder, der eine kaiserliche Standeserhöhung erhielt und sich in „seinem“ Land dieser bedienen wollte, hatte der landesfürstlichen Regierung Mitteilung davon zu machen. Diese wiederum hatte den Adel anzuerkennen oder dem kaiserlichen Hofe ihre Bedenken kundzutun. Solche landesherrliche Ausschreibungen gab es in den verschiedensten Territorien: Mecklenburg-Schwerin (einmalig 1530, dann ab 1667), Kursachsen (1628), Preußen (1654), Sachsen-Weissenfels (1673), Sachsen-Merseburg (1685), Sachsen-Zeitz (1702), Kurbraunschweig-Lüneburg (1706), Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1794) und Baden (1805)

(…)

Die Widersprüche zwischen gesatztem Reichsrecht und faktischer Entwicklung haben natürlich auch zeitgenössische Juristen bewegt. Während noch im 17. Jahrhundert das ausschließliche Recht des Kaisers (und der von ihm Ermächtigten) zur Nobilitierung zumindest in den deutschsprachigen Gebieten weitgehend unbestritten gewesen sein dürfte, brach im 18. Jahrhundert der Disput voll aus. Die Palette reichte damals vom Negieren der Vornahme von Adelsverleihungen durch einzelne Reichsfürsten bzw. die klare Verteidigung des kaiserlichen Reservatrechtes (Steck, Riccius, Zeiller) über eine neutrale Position (Bilderbeck, Moser), das schlichte Konstatieren landesfürstlicher Verleihungen (Kreittmayr), die Anerkennung des landesfürstlichen Rechtes zur Adelsverleihung mit Beschränkung der Gültigkeit auf das eigene Territorium (Klaute) und die Verteidigung der landesfürstlichen Berechtigung zur Adelsverleihung (Pfeffinger, Struve, Müller) bis zu einer derart heftigen Bekämpfung eines kaiserlichen Reservatrechtes, daß als Resultat den Markgrafen von der Lausitz mehr Rechte zustehen sollten als dem Kaiser (sic!) (Troppaneger). Die Rechtsfrage der Gültigkeit der Verleihungen „aus landesfürstlicher Macht“ blieb so bis zum Untergang des alten Reiches ungeklärt und war am Ende wohl auch weniger eine Rechtsfrage als vielmehr eine Machtfrage.

Een interessant voorbeeld is de familie Von Weiler. Bij diploma van koning Friedrich Wilhelm II van Pruisen van 31 januari 1787 werd de adeldom van Arnold Weiler bevestigd en werden hij en zijn wettige nakomelingen verheven in de adel van het koninkrijk Pruisen. In 1818 werd de familie ingelijfd in de Nederlandse adel (bron: Nederland’s adelsboek).

De door Frölichsthal geconstateerde problematiek kan dus niet met wat eenvoudige redeneringen worden oplost. Duidelijk is wel dat hoewel het rijksadelsdiploma van de familie Quast over een verheffing spreekt, dit niets over oorspronkelijke adel van de familie zegt. De enige conclusie die getrokken kan worden is dat de regionale adeldom van de familie niet formeel binnen het Heilige Roomse Rijk werd erkend. Materieel wellicht wel omdat iets meer dan een jaar later de geadelde zonder enige aanleiding werd verheven tot “Freiherr”. Kennelijk werd de eerste verheffing in de adel toch als een te geringe verheffing gezien.

Echtpaar Quast – Von Bocholtz

In het bekende werk van A. Fahne over de familie Von Bochholtz, ontbreekt het echtpaar Joachim von Quast – Catherina von Bochholtz. Hoewel dit jammer is, zegt dit verder niets. De daarin opgenomen gegevens hoeven immers niet compleet te zijn. Het is zelfs volstrekt onrealistisch te denken dat de honderden jaren beslaande genealogie van Fahne compleet is. Ook aan de kwaliteit van het werk van Fahne werd destijds als getwijfeld (de.wikipedia.org, artikel Anton Fahne):

Schon in der sogenannten zweiten Abtheilung des Ersten Heftes (Erster Jahrgang) der Annalen des historischen Vereins für den Niederrhein aus dem Jahr 1855 wird Fahne herbe Kritik wegen seiner Veröffentlichung Die Dynasten, Freiherrn und Grafen von Bocholtz nebst Genealogie derjenigen Familien, aus denen sie ihre Frauen genommen mit urkundlichen Belegen von A. Fahne von Roland, Band 3, Chronik der Abtei Gladbach = Chronica abbatiae Gladbacensisa zuteil.

Catharina von Bocholtz die genoemd is in de handschriftgenealogie in het familie-archief Quast is wellicht identiek aan een Catharina von Bocholtz die in de collectie Generalleutnant E.A.A.A. von Oidtman (1854-1937) wordt genoemd. In deze omvangrijke genealogische collectie, die zich bevindt zich in de universiteitsbibliotheek in Keulen bevindt, wordt dus in ieder geval gedeeltelijk ondersteuning gevonden voor de feiten die in de handschrift-genealogie zijn opgenomen. In Nederlandse Genealogien 11 wordt verwezen naar de collectie Oidtman in eindnoot 5.

A. Fahne, Die Dynasten, Freiherren und jetzigen Grafen von Bocholtz, Beitrag zur alten Geographie, Rechts-, Sitten- und Culturgeschichte der Niederrheins, Keulen 1859, 1863.

Alexander Hume, of Manderstone, de jure Earl of Dunbar

George Home, 1st Earl of Dunbar (c.1556–1611) was, in the last decade of his life, the most prominent and most influential Scotsman in England. His work lay in the King’s Household and in the control of the State Affairs of Scotland and he was the King’s chief Scottish advisor. With the full backing and trust of King James he made an impressive — yet brief — career, veering from London to Edinburgh via Berwick-upon-Tweed with astonishing regularity. Home was the son and third child of Sir Alexander Home of Manderston, Berwickshire, and was introduced, at the early age of 26, to the Court of sixteen-year-old James VI by a relative, Alexander Home, 6th Lord Home. On 7 July 1604 he was created Baron Hume of Berwick in the Peerage of England. In 1605 he was created a Knight of the Garter, and, on 3 July 1605, Earl of Dunbar in the Peerage of Scotland.

Subsequent claimants to the title

- John Home, de jure 2nd Earl of Dunbar (a 1628), brother of 1st Earl, according to the Lord Advocate in 1634, he “conceiving his fortune too mean, forebore to assume the dignity”. He died without male issue.

- George Home, de jure 3rd Earl of Dunbar (a 1637), son of Alexander Home of Manderston and nephew of 1st Earl, certified in his claim in 1634 by the same Lord Advocate.

- Alexander Home, de jure 4th Earl of Dunbar (d 1675), son of 3rd Earl, said to have been confirmed in title by Charles II in 1651 but which does not appear in The Great Seal of Scotland. Died without male issue.

- Alexander Hume, of Manderstone, de jure 5th Earl of Dunbar (b. 1651, d. 4 Jan. 1720 Aurich, Germany (nephew of 4th Earl. Capt. of a troop of horse in the service of the States of Holland. To him 14 Oct. 1689, King William III. confirmed the Earldom of Dunbar exemplifying the previous confirmation thereof by Charles II.

It is not known if Alexander Hume styled himself “Earl of Dunbar” in Germany (Ostfriesische Landschaft, Biographisches Lexikon fuer Ostfriesland, 177938/622/23814). His son – Leonard Hume, de jure 6th Earl of Dunbar – inherited the estate in Stikelkamp from his father (4). Leonard’s son – Heeres Andries Hume – was de jure the 7th Earl of Dunbar (b. 1738 in Norden). He married Antje van Bergen. After this marriage the family name converted to Van Bergen.

No claimant has progressed his claim before the House of Lords Committee for Privileges to a satisfactory conclusion. This Committee was – until the Dissolution of Parliament on 12 April 2010 – the only body which was authorised to decide whether or not a claimant may be confirmed in the title. The usual way to establish the right to inherit a title is to apply for a Writ of Summons to attend Parliament (a procedure that will have to be reviewed in the light of new legislation abolishing the hereditary parliamentary rights of peers). Then the Committee for Privileges examines the validity of the documentation supporting the line of descent of the claimant and his relationship to the previous holder of the peerage title.

First Generation

Alexander HUME OF MANDERSTONE was born in 1651 and died on 4 Jan 1720 in Aurich. He was buried on 26 Jan 1720 in Aurich (Germany). Alexander married lsabella Cornelia FEWEN, daughter of Dr Leonard FEWEN and Susanne MAMUCHET VAN HOUDRINGEN on 22 Mar 1673 in Leeuwarden. lsabella was born in 1662 and died in 1723.

Alexander and lsabella had the following children:

- Leonard HUME OF MANDERSTONE, born on 29 May 1684, died on 2 Feb 1741.

- Habbo Marcus HUME OF MANDERSTONE, born on 9 Sep 1676, died about 1676.

- Susanna Hesther HUME OF MANDERSTONE, born on 23 Oct 1677, died on 7 Mar 1726.

- Maria Isabella HUME OF MANDERSTONE, born on 17 Dec 1679, died about 1679.

- Agatha Isabella HUME OF MANDERSTONE, born on 28 Mar 1681.

- Georgetta Leonarda HUME OF MANDERSTONE, born on 4 Feb 1683, died about 1683.

- George Christian HUME OF MANDERSTONE, born in Apr 1686, died in 1706.

- Alexander HUME OF MANDERSTONE, born on 18 Aug 1674, died issue-less in 1703.

- Albertina Mechteld HUME, born on 5 Jan 1688, died on 28 Jun 1733 in Hesel. She was buried on 8 Aug 1733 in Twixlum. Albertina married Arend Jan VON LOUWERMAN on 16 Jun 1730 in Wirdum.

Second Generation

Leonard HUME OF MANDERSTONE, born on 29 May 1684 in Uttum, die on 2 Feb 1741 in Stikelkamp. 6. Earl of Dunbar, Baron Hume, of Berwick. Leonard married Gesina BRUCKEN before 1721. Gesina was born in 1701 and died on 20 Sep 1763 in Stikelkamp. She was buried on 24 Sep 1763 in Hesel. Leonard and Gesina had the following children:

- Heero Andries HUME, born in 1738.

- Helene HUME, died on 20 May 1784.

- Susanna Hesther HUME OF MANDERSTONE, born on 23 Oct 1677, died on 7 Mar 1726. Susanna married Julius Anton VON CAPELLE, son of Christoph VON CAPELLE and Margaretha VON MANDELSLOH on 2 Jul 1710. Julius was born on 12 Oct 1681 and died on 8 Sep 1776. He was buried Funnix. They had the following children: (i) Capt. in the service of the States of Holland Alexander VON CAPELLE, born in 1713 and died 1772 in Nijmegen. (ii) Christoph VON CAPELLE, born in 1715, died in Batavia.

Third Generation

- Heero Andries HUME (assumed the name VAN BERGEN: Ahnenpass), born in 1738 in Norden (Hannover, personal union with Great Britain), died Norden, de jure 7. Earl of Dunbar, Baron Hume, of Berwick. Heero Andries married Antje Christiaans VAN BERGEN in 1765 in Norden, daughter of Christiaan VAN BERGEN and Ann HUME. Antje was born and died in Norden (Overlijdensregister 1847; aktenummer 45; Gemeente Midwolda; Periode 1847; Jim Roy Hume, email 18 March 2000). Their son: Andries Heeres VAN BERGEN was born on 30 Dec 1768 in Oldersum. He died on 7 Jul 1847 in Midwolda (Literature regarding his descendants: Kwartierstatenboek: verzameling kwartierstaten bijeengebracht ter gelegenheid van de herdenking van het 110-jarig bestaan van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Genootschap voor Geslacht- en Wapenkunde, 1883-1993).

- Helene HUME, died on 20 May 1784 in Stikelkamp. Helene married Hofgerichtsprocurator, Kgl. Preuss. Kriminalrath zu Aurich Bebaeus Scato KETTWIG, son of Peter Janssen KETTWIG and Johanna Isabella GOCKINGA. Bebaeus died on 29 Apr 1777. They had the following children: (i) Isabella Johanna Cornelia KETTWIG was born on 21 Feb 1742. Isabella married Kriegsrat LANTZIUS-BENINGA on 14 Jan 1744. (ii) Peter Janson KETTWIG was born in 1744.

- Nationaal Archief, inventarisnummer 2.21.008.01, Inventaris van het archief van de familie De Constant Rebecque, 133 Stukken betreffende de familie Hume van Dunbar (de echtgenote van Julius Anthon von Capelle was Susanna Hester Hume).

- MSS of Colonel Mordaunt-Hay of Duns Castle, Historical Manuscripts Commission, collection no. 5, 1909, page 66, number 180. The lordship George Home, Earl of Dunbar, is cited as deceased, and although the daughters are mentioned, there are no indications of either of them assuming the peerage.

- Stadt Archiv Aurich, Dep. 40, Nr. 6, 13 und 13 a.; Quellen: StAA, Rep. 100.

- Archief Raad van State, inv. no. 1527, p. 78.A: “Sir Alexander Hume, ridder, volgt wijlen kapitein James Balfour 16 november 1643 op Groninger Archieven.

- Ahnenpass of Tjapko Antoon van Bergen, member of the Dutch Olympic Rowing Team 1928. T.A. van Bergen served as SS-Rottenführer in the second World War. His grave can be found on www.volksbund.de/graebersuche.

- Family Search, LDS Church, IGI Individual Record, 178004/405/13493.

Literature

Paul, J. B. (2016). Scots Peerage: Founded on wood’s edition of sir Robert Douglas’s Peerage of Scotland; … Edinburgh, David Douglas, 1906 (classic reprint). FORGOTTEN Books.

Suchfrage in: Quellen und Forschungen zur Ostfriesischen Familien- und Wappenkunde 16 (1967), p. 50.

Jansen, L. and H.R. Manger, Die Familien der Kirchengemeinde Hesel (1643-1900) (Aurich 1974), p. 400.

“XII. GEORGE HOWME, Knt., High Treasurer of Scotland was on 7 July 1604, Cto II BARON HUME (Howme), OF BERWICK ” [S.], with rem. to his heirs for ever.(a) Shortly afterwards he was as ” Lord Home of Berwick in England ” [sio but query] by patent dat. at Windsor,3 July 1605, cr. EARL OF DUNBAR [S.], with rem. to his heirs male.(b) He was 4th and yet. s. of Alexander HOME, or HUME, of Manderston, co. Berwick, by Janet, da. of George HOME, or HUME, of Spot; was a Gent. of the Bedchamber to King James VI [S.], in 1585, by whom he was Knighted, in 1590 ; Master of the Wardrobe, 1590, and High Treasurer [S.], 5 Sep. 1601. Attending the King into England, he was made P.C., in 1603, and in the next year cr. a Peer as above stated. Chancellor of the Exchequer [S.] ; High Commissioner to the general essembly [S.], 1606.10, being employed by the King for the restoration of episcopacy in Scotland; el. KG. 23 April and inst. 18 May 1608. He m.. Catharine, da. of Sir Alexander GORDON, of Gight, by Mary, da. of Cardinal David BETOUN, Archbishop of St. Andrew’s [8.] He d. s.p.m. at Whitehall somewhat suddenly 29 Jany. 1611/2, since which time hia honours have remained dormant.He was bur. at Dunbar. M.I. The right to the Earldom of Dunbar, tho´ unquastionably still remaining has never been fully recoginised since the death of the grantee of 1605. It appears to be as under. XIII. JOHN (HOME), EARL OF DUNBAR [8.1, next elder br. and (more Scotico) heir, being 3d s. of his father abovenamed. He d. s.p. 1614. XIV. 1614. DAVID HOME living 1571 (but who apparently d. s.p.) was the next eldest br. while ALEXANDER HOME, of Manderston, was the elder br. of the 1st Earl, but whether either of these were alive in 1614 is unknown. Sir GEORGE HOME, of Manderston, only s. and h. of the latter was living in 1631, and one of these three must, apparently, from 1614 have been de jure EARL OF DUNBAR. On 6 Aug. 1634, the Lord Advocate [S.] certified to the King that that dignity ” lawfully descended ´to the above’ named Sir George Home, the collateral male heir, and failing him that it would devolve upon Sir Alexander Home, then at the Hague. The said George d. before 1651. XV1651 SIR .ALEXANDER HOME heir male (probably s. and h. of the(b) above); sometime in the service of the Princess of Orange at Hague. To him on 6 May 1651, Charles II. confirmed the Earldom of Dunbar. He d. s.p.m. before 1689. XVI. 1689 ALEXANDER HOME, of Manderston afsd., Capt. of a troop of horse in the service of the 8tates of Holland, nephew and h. male of the above. To him 14 Oct. 1689, King William III. confirmed the Earldom of Dunbar exemplifying the previous confirmation thereof by Charles II. The family is said to have resided in Holland and to have there become extinct in the male line during the 17th century.“.

Arbeitsgruppe Familienkunde und Heraldik, Ostfriesischen Landschaft. Quellen und Forschungen zur Ostfriesischen Familien- und Wappenkunde, 13. Jahrgang (1964) Heft 3, Seite 26; Arbeitsgruppe Familienkunde und Heraldik, Ostfriesischen Landschaft “Zur C.”:

Zur Charakterisierung der Verhaeltnisse dieser Familie von Capelle moege noch ein bezeichnender Vorfall Platz finden: Hume of Manderstone starb am 4. Januar 1720 zu Aurich arm und mit seiner Frau Isabella Cornelia, geb. Fewen, zerfallen. An Humes Todestage liesz dessen an J .A. v .Capelle verheiratete Tochter Susanne, die in den traurigsten Verhaeltnissen lebte und ebenfalls mit ihrer Mutter auf gespanntem Fusze standt beim Hofgericht die Versiegelung der in der Wohnung ihres Vaters befindlichen Papiere beantragen. Da die Witwe unter dem Vorgeben, dasz sie kein bares Geld besitze, sich weigerte, die Beerdigungskosten zu tragen, so verfuegte der Fuerst am 26. Januar (drei Wochen nach Humes Tode), dasz noch selbigen Abends die Beerdigung unter Begleitung des Auricher Militars mit 24 Fackeltraegern stattzufinden habe. Dies geschah auch. Die Kosten im Betrage von 31 Thalern und 11 Schillingen bezahlte die Witwe , die zu Stickelkamp wohnte ( . . . . ) , nachdem ihr die Rechnung mit Androhung der Exekution zugeschickt worden war”

Joseph König, Verwaltungsgeschichte Ostfrieslands bis zum Aussterben seines Fürstenhauses (Veröffentlichungen der nieders. Archivverwaltung, 2), Göttingen 1955.

John Burke, A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire, 6. Ed., London 1840, p. 545.

K.B. Haan, De Kokkengieters van Bergen, Van Midwolda naar Heiligerlee.

Koninklijk Nederlandsch Genootschap voor Geslacht- en Wapenkunde, De Nederlandsche Leeuw , Jg. 37 ( 1919), kolom. 329:

“Alexander Hume of Manderstone(earl of Dunbar) geb. 1651, t Aurich 4 Jan. 1720, zoon van George, kapitein in Nederlandschen dienst en Hester van Loo. Hij was in Oostfrieschen dienst, sedert 26 Juli 1676 drost van Gretsiel, 1692-1716 drost van Aurich, 5 Jan. 1693 benoemd tot geheimraad. Hem werden meerdere malen diplomatieke zendingen opgedragen, o.a. naar Engeland, tr. 1673 lsabella Comaelia Fewen, geb. 1662, t . . . . 1723, dr. van Leonhard Fewen, vertegenwoordiger te Emden (1662), burgemeester aldaar 1670-72, vorstelijk Kamerrat, overl. 3 Juli 1681 op zijne bezitting bij Twixlum. Hij huwde te Leiden 14 Juni 1633 Susanna Mamuchet, geb.te Utrecht, dochter van Marcus Mamuchet. (Vgl. XxX1.) (1)Uit dit huwelijk negen kinderen. Zie verder de uitvoerige beschrijving van dit echtpaar en hunne kinderendoor Kar1 Herquet in zijn: Miscellen zur Geschichte Ost-frieslands. Het derde kind: Susanna Hume of Manderstone, geb. 23 Oct. 1677, overl. 7 Maart 1726, tr. 2 Juli 1710 Julius Anton van Capelle. Vgl. Nederland’s Adelsboek 1913 blz. 23, alwaar hare moeder ten onrechte van Fiwen wordt genoemd.”Burgerlijke Administratie Leeuwarden, Friesland (LDS Family Group Record).

Ostfriesische Landschaft, Biographisches Lexikon fuer Ostfriesland , 177938/622/23814.”Stikelkamp blieb im Besitz seines Sohnes Leonard.”:

“HUME OF MANDERSTONE, Alexander geb. 1651 gest. 4.1.1720 Aurich Geheimrat; ev. Die Fürstin Christine Charlotte von Ostfriesland nahm mehr Ausländer in ihre Dienste, als man bisher gewohnt war. Zu diesen Personen zählte Hume (englisch Home), Abkömmling einer schottischen adligen Familie, dessen Großvater Hofmeister der Prinzessin Maria Stuart, Gemahlin des holländischen Erbstatthalters Wilhelm II. gewesen und mit der Familie in den Niederlanden geblieben war. Wahrscheinlich war aber auch der ererbte Besitz verschuldet und schwerlich wiederzuerlangen; jedenfalls hat Hume den ihm zustehenden Titel eines “Earl of Dunbar” in Ostfriesland nicht geführt.Hume muß ein wendiger und begabter Mensch gewesen sein. 1675 wurde er Drost des Amtes Greetsiel und war als solcher nicht auf seinem Posten, als 1682 die Brandenburger Greetsiel überfielen und einnahmen. Seiner Karriere hat das nicht geschadet: 1692 wurde er Drost des Amtes Aurich und 1693 gleichzeitig Mitglied des Geheimen Rates. Dies war eine Ehrenstellung, wie es das Drostenamt zu werden drohte, und verpflichtete nicht zu dauernder Mitarbeit in der Regierung. Aber der Auricher Drost war sowieso in der Residenz anwesend. Gewiß wird Hume aber bestimmte Aufgaben erledigt haben. Es wäre übertrieben, ihn als eine Art “Außenminister” anzusehen, doch machten ihn seine englischen Verbindungen für das FürsteThe Scots Peerage Volume III Dunbarnhaus zu einem geeigneten Verhandlungspartner mit König Wilhelm III. von Großbritannien, der holländischer Erbstatthalter geblieben war. Beispielsweise stellte Ostfriesland 1703 Freiwillige für ein Regiment, das die Niederlande imspanischen Erbfolgekrieg einsetzten und bezahlten.Über seine Frau Isabella Fewen hatte Hume die ehemalige Johanniterkommende Stikelkamp geerbt. Der Ausbau des zugehörigen Fehns muß mit dem gemeinsamen Vermögen auch die Ehe zerrüttet haben. 1716 trat Hume von allen Ämtern zurück und starb vereinsamt. Stikelkamp blieb im Besitz seines Sohnes Leonard.

Paechter und Ertraege des Gutes Stikelkamp in Quellen und Forschungen zur Ostfriesische Familien- und Wappenkunde 10 (1961), p. 13).

K.B. Haan, De klokkengieters Van Bergen. Van Midwolda naar Heiligerlee 1795 – 1980, Heiligerlee, 1992: VAN BERGEN Wapen. In blauw een zilveren duif op een een groene berg. Dekkleden: rood, zilver. Helmteken: drie gouden korenaren. Dit wapen wordt gevoerd door het Hamburgse patriciersgeslacht Von Bergen (E.L. Lorenz-Meyer, Hamburgischer Wappenrolle, Hamburg 1912).

De aan het einde van de achttiende eeuw in Nederland gevestigde leden gingen zich – vanaf de tweede generatie hier te lande – Van Bergen noemen in plaats van Von Bergen, en waren voornamelijk werkzaam als scheepsbouwer. Zij legden zich echter sinds 1795 toe op het gieten van luidklokken voor de drie noordelijke provincies en het noordelijke deel van Duitsland. De klokken waren destijds grotendeels bestemd voor de Nederlandse Hervormde kerken waar men ze ten behoeve van de eredienst en openbare tijdsaanduiding gebruikte (Haan 1992, p. 7). In de stroom van de voortschrijdende industrialisatie bouwde de familie in 1862 een fabriek in Heiligerlee (later de firma Koninklijke A.H. van Bergen). Nakomelingen maakten zich vanaf de jaren dertig van de negentiende eeuw bijzonder verdienstelijk met het maken van carillons en wisten er een wereldwijde faam mee op te bouwen (Haan 1992, p. 8). In verband met een levering aan de koning van Pruisen werden door hem twee gouden pistolen geschonken met daarin gegraveerd het genoemde familiewapen. Andere takken van het geslacht voeren afwijkende helmtekens, zoals drie rozen en drie struisvogelveren. De fabrikant Andries Heero van Bergen, heer van Oosterbroek (geb. Midwolda 1 maart 1835, overl. Eelde, havezathe Oosterbroek 18 sept. 1913) tekende de genealogie van het geslacht op in zijn Geslachtslijst van de Familien von Bergen, Midwolda 1861. Op zijn ex libris is het hiervoor genoemde wapen afgebeeld.

Joseph König, Verwaltungsgeschichte Ostfrieslands bis zum Aussterben seines Fürstenhauses (Veröffentlichungen der nieders. Archivverwaltung, 2), Göttingen 1955.

Roll of eminent burgesses of Dundee, 1513-1886. (1961). Salt Lake City, UT: Filmed by the Genealogical Society of Utah.

Sir Alexander Hume of Manderstone – 16th October 1621

WHICH DAY SIR ALEXANDER HOME OF MANDERSTON is MADE A BURGESS AND BROTHER OF THE GUILD OF DUNDEE, GRATIS.

SIR ALEXANDER HOME was descended from SIR DAVID HOME of Wedderburn, who fell at Flodden, his great-grandfather having been SIR ALEXANDER of Manderston, the third son of SIR DAVID, and one of the famous “Seven Spears of Wedderburne.” He was the brother of SIR GEORGE HOME, Knt., Lord Treasurer of Scotland, who was created a Peer in England with the title of BARON HUME of Berwick, in 1604, and raised to the dignity of EARL OF DUNBAR in Scotland in the succeeding year. Both these titles became extinct on the death of SIR GEORGE, without male issue, in 1611. The HOMES of Manderston were connected with Dundee through their intermarriages with the WEDDERBURNS of Gosford and Kingennie.

Lantzius-Beringa, Nota zur Familie Fewen, in Quellen und Forschungen zur Ostfriesische Familien- und Wappenkunde 17 (1968), p. 92, Karl Herquet, Miscellen der Geschichte Ostfrieslands, 100.

Herquet, K. (1985). Miscellen zur Geschichte Ostfrieslands. Vaduz / Liechtenstein: Sändig.

R., J. L. (2009). Die Familien der Kirchengemeinde Hesel (1643-1900). Aurich, Ostsfriesland, Germany: Upstalsboom-Gesellschaft, p. 326.

From History of Dunbar Hume and Dundas from Drummond’s Noble British Families, William Pickering, London 1846 “Alexander got the lands of Manderston from George 4th Lord Home, and Coldingham.”

Taylor, James, The Great historic families of Scotland. London: J.S. Virtue & Co., 1887 (OCoLC)892838853.

Burke’s Peerage, Burke’s Peerage Limited, London, 1949, 99th Edition “Ancestor of the Earl of Dunbar and the Home Baronets of Renton.”

Drummond, Henry. Histories of Noble British Families, with Biographical Notices of the Most Distinguished Individuals in Each, Illustrated by their Armorial Bearings Protraits Monuments Seals Etc. (Part VI, London, William Pickering, 1844, (Folio), pp. 1-44.), page 20 and 28. FHC Microfilm # 0990417

The Lineage and Ancestry of H.R.H. Prince Charles, Prince of Wales, Edinburgh, 1977, Paget, Gerald, Reference: N 14393

Appendix: The great historic families of Scotland

Taylor, James, 1813-1892. Great historic families of Scotland. London : J.S. Virtue & Co., 1887 (OCoLC)892838853.

Hume Family Home Page – The Great Historic Families of Scotland

369

THE HOMES

THE Homes are among the oldest and most celebrated of the historical families of Scotland. Their founder was descended from the Earls of Dunbar and March, who sprung from the Saxon kings of England and the princes of Northumberland. After the conquest of that country by William of Normandy, Cospatrick, the great Earl of Northumberland, and several other Saxon nobles connected with the northern counties, fled into Scotland in the year 1066, carrying with them Edgar Atheling, the heir of the Saxon line, and his two sisters, Margaret and Christina. Malcolm Canmore, who married the Princess Margaret, bestowed on the expatriated noble the manor of Dunbar, and broad lands in the Merse and the Lothians. Patrick, the second son of the third Earl of Dunbar, inherited from his father the manor of Greenlaw, and having married his cousin Ada, daughter of the fifth Earl by his wife, a natural daughter of William the Lion, obtained with her the lands of Home (pronounced Hume), in Berwickshire, from which the designation of the family was taken. The armorial bearings of his ancestors, the Earls of Dunbar, which were a white lion on a red field, were assumed by him on a green field for a difference, referring to his paternal estate of Greenlaw.

Under the protection of their potent kinsman, the De Homes flourished and extended their possessions, and kept vigilant ‘watch and ward’ on the Eastern Marches against the incursions of the Northumbrian freebooters. One of their chiefs, a Sir John de Home, was so conspicuous for his successful forays across the Border, always fighting in a white jacket, that he obtained from the English the sobriquet of ‘Willie with the White Doublet.’ The son of this redoubtable Border chief acquired the estate of Dunglass (from which the second title of the family is taken) by his marriage to the

370 [Hume/Home Crest]

371 The Homes

heiress of Nicholas Pepdie, in the reign of Robert III. The second son of this couple was the founder of the warlike family of Wedderburn, from which the Earls of Marchmont are descended.

Hitherto the De Homes had acknowledged as their feudal lords the Earls of Dunbar and March, the heads of the great house from which they sprung, who, from their vast possessions and their strong castle of Dunbar, on the eastern Border, having the keys of the kingdom at their girdle, as they boasted, were among the most powerful nobles in the kingdom. Partly from ambition, partly, it would appear, from a hereditary fickleness of character, these barons were noted for the frequency with which they changed sides in the wars between England and Scotland. The eleventh Earl was in the end unfairly deprived of his earldom, castles, and estates by James I., towards the middle of the fifteenth century, in pursuance of his policy to break down the power of the great nobles. As some compensation for this treatment, the King conferred upon him the title of Earl of Buchan, but he indignantly refused to accept of the honour, and sought an asylum in England, from which he never afterwards returned. His father, the tenth Earl of Dunbar and March, who was one of the heroes of Otterburn, in consequence of the manner in which the contract of marriage between his daughter and the Duke of Rothesay was broken off (see THE DOUGLASES), renounced his allegiance for a time to his sovereign; the De Homes, his kinsmen, abandoned his banner, and fought against him and Harry Percy at the sanguinary battle of Homildon, where their chief, SIR ALEXANDER HOME, was taken prisoner. On regaining his liberty he accompanied the Earl of Douglas (Shakespeare’s Earl, nicknamed Tineman) to France, shared in his triumphs and disasters, and fell along with him at the battle of Verneuil, in 1424, where the Scottish auxiliaries were almost annihilated. Sir Alexander’s second son, THOMAS, was the ancestor of the Homes of Tyningham and the Humes of Ninewells, the family of which David Hume, the philosopher and historian, was a member.

After the final overthrow of the Earls of Dunbar and March, in January, 1436, the Homes succeeded to a portion of their vast estates, and to a great deal of their power on the Borders as Wardens of the Eastern Marches. SIR ALEXANDER HOME, the head of the family, was created a peer by the title of LORD HOME, 2nd August, 1473, and seems to have possessed considerable diplomatic ability, as he was frequently employed by James III. in carrying out important negotiations with

- The Great Historic Families of Scotland

the English Court. His father and his uncle had held in succession the office of bailie of the lands belonging to the monastery of Coldingham, and he induced the prior and chapter to make the office hereditary in his family. He exerted all his influence in that situation to obtain possession of the large conventual property, and indeed seized and appropriated it to his own use. He was, therefore, greatly irritated by the attempt of King James, with the consent of the Pope, to attach the revenues of the priory to the Chapel Royal at Stirling, and joined the disaffected nobles in their conspiracy against that ill-fated sovereign. His Border spearmen contributed not a little to the defeat and death of James at Sauchie. The Homes obtained a liberal share of the fruits of the victory gained by the rebellious barons. The revenues of Coldingham, the prize for which Lord Home had rebelled and fought against his sovereign, were allowed to remain in his possession, and ALEXANDER HOME, second baron, his grandson and heir, was appointed immediately after the murder of James to the office of Steward of Dunbar, and obtained besides a large share of the administration of the Lothians and Berwickshire. He was also sworn a Privy Councillor in 1488, and was appointed for life to the important office of Great Chamberlain of Scotland. In 1489 he was nominated Warden of the East Marches for seven years, and at the same time was made captain of the castle of Stirling, and governor of the young King. The tuition of John, Earl of Mar, the brother of James IV., was likewise committed to this potent noble. He obtained also a charter of the bailiery of Ettrick Forest, and in the following year was appointed by the Estates to collect the royal rents and dues within the earldom of March and barony of Dunbar. In 1497 Lord Home repaired to the royal standard with his retainers when James IV. invaded England in support of the pretensions of Perkin Warbeck. In retaliation for his ravages in Northumberland and Durham, an English army, under the Earl of Surrey, laid waste the estates of the Homes, and ‘demolished old Ayton Castle, the strongest of their forts,’ as Ford terms it, in his dramatic chronicle of ‘Perkin Warbeck.’

The Homes had now gained a position in the foremost rank of the great nobles of Scotland, and ALEXANDER, the third lord, who succeeded to the vast estates of the family in 1506, elevated them to the highest summit of rank and power ever attained by their house. In 1507 he was appointed to the office of Lord Chamberlain, which

- The Homes

had been held by his father, and succeeded him also in the warden-ship of the Eastern Marches.

When war was about to break out between James IV. and his brother-in-law, Henry VIII., Lord Home, at the head of three or four thousand men, made a foray into England and pillaged and burned several villages or hamlets on the Borders. On their return home laden with booty, and marching carelessly and without order, the invaders fell into an ambush laid for them by Sir William Bulmer among the tall broom on Millfield Plain, near Woolet, and were surprised and defeated with great slaughter. According to the English chronicler, Holinshead, five or six hundred were slain in the conflict, and four hundred were taken prisoners, among whom was Sir George Home, the brother of Lord Home. Buchanan, however, estimates the number of prisoners at two hundred, and says that it was the rear only which fell into the ambuscade, while the other portion of the force with their plunder arrived safely in Scotland.

This mortifying reverse deeply incensed the Scottish king, and made him doubly impatient to commence hostilities in order to avenge the defeat sustained by his Warden.

When James took the field shortly after, Lord Home brought a powerful array of his followers to the royal banner, in that campaign which terminated in the fatal battle of Flodden. The Homes and the Gordons, under Lord Huntly, formed the vanguard of the Scottish army in that engagement, and commenced the battle by a furious charge on the English right wing, under Sir Edmund Howard, which they threw into confusion and totally routed. Sir Edmund’s banner was taken, he himself was beaten down and placed in imminent danger, and with difficulty escaped to the division commanded by his brother, the Admiral. The old English ballad on ‘Flodden Field’ thus describes Home’s attack on the English vanguard:—

‘With whom encountered a strong Scot,

Which was the King’s chief Chamberlain,

Lord Home by name, of courage hot,

Who manfully marched them again.

‘Ten thousand Scots, well tried and told

Under his standard stout he led;

When the Englishmen did them behold

For fear at first they would have fled.’

Lord Dacre, who commanded the English reserve, however, advanced to Sir Edmund’s support, and kept the victorious Homes and Gordons

- The Great Historic Families of Scotland

in check. He states, in a letter to the English Council, dated May 17th, 1514, that on the field of Brankston he and his friends encountered the Earl of Huntly and the Chamberlain; that Sir John Home, Cuthbert Home of Fast Castle, the son and heir of Sir John Home, Sir William Cockburn of Langton, and his son, the son and heir of Sir David Home [of Wedderburn], the laird of Blacater, and many other of Lord Home’s kinsmen and friends, were slain; and that on the other hand Philip Dacre, brother of Lord Dacre, was taken prisoner by the Scots, and many other of his kinsfolk, servants, and tenants, were either taken or slain in the struggle. Sir David Home of Wedderburn had seven sons in the battle, who were called ‘The Seven Spears of Wedderburn.’ Sir David himself and his eldest son, George, fell in the conflict with Lord Dacre. These facts completely disprove the charge made against the chief of the Homes that he remained inactive after defeating the division under Sir Edmund Howard. It is alleged, however, by Pitscottie, that when the Earl of Huntly urged Lord Home to go to the assistance of the King, he replied, ‘He does well that does well for himself; we have fought our vanguard and won the same, therefore let the lave [rest] do their part as well as we.’ This statement, however, is in the highest degree improbable, and is directly at variance with the account which Lord Dacre gives of his conflict with the Homes, after they had defeated Sir Edmund Howard’s division. It seems to have been invented by the enemies of Home, who, though he fought with conspicuous courage in the battle, incurred great odium in consequence of his having returned unhurt and loaded with spoil* from this fatal conflict. It was even alleged that he had carried off the King from the battlefield and afterwards put him to death. A preposterous story passed current among the credulous of that day that in the twilight, when the battle was nearly ended, four horsemen mounted the King on a dun hackney and conveyed him across the Tweed with them at nightfall. From that time he was never seen or heard of, but it was asserted that he was murdered either in Home Castle or near Kelso by the vassals of Lord Home. This absurd tale was revived about fifty or sixty years ago by a popular writer, who gave credit to a groundless rumour that a skeleton wrapped in a bull’s hide and surrounded with an iron chain had been found in the well of Home Castle. Sir Walter Scott says he could never find any

- The baggage-waggons were drawn up behind Edmund Howard’s division – a fact which may account for the Borders having secured so much spoil.

- The Homes

better authority for the story than the sexton of the parish having said that if the well were cleaned out he would not be surprised at such a discovery. Lord Home had no motive to commit such a crime. He was the chamberlain of the King, and his chief favourite; and, as it has been justly remarked, he had much to lose (in fact, did lose all) in consequence of James’s death, and had nothing earthly to gain by that event.

Six months after the battle of Flodden, Lord Home was nominated one of the standing councillors of Queen Margaret, who had been chosen Regent, and was also appointed Chief Justice of all the country south of the Forth. He was deeply implicated in all the intrigues of that turbulent and factious period of Scottish history, and was alternately on the side of the Queen Dowager and of Albany, who succeeded her as Regent after her marriage to the Earl of Angus. He protected Margaret in her flight into England in 1516, and concocted with Lord Dacre measures to overthrow the Government of the Regent. In revenge for these proceedings Albany marched into the Merse at the head of a powerful army, overran and ravaged Home’s estates, captured Home Castle, his principal stronghold, and razed Fast Castle, another of his fortalices, to the ground. Under pretence of granting him an amnesty and a pardon, Albany induced Home to meet him at Dunglass, where he was treacherously arrested and committed a prisoner to the castle of Edinburgh, then under the charge of the Earl of Arran, his brother-in-law. He contrived, however, to prevail on Arran, not only to let him escape from prison, but to accompany him in his flight into England. A few months later Home made his peace with the Regent and was restored to his estates on condition that if ever he rebelled again he should be brought to trial for his old offences. But, unmindful of the warning he had received, and disregarding his promise, he speedily renewed his treasonable intrigues with Lord Dacre, the English Warden, who hired Home’s retainers to plunder and lay waste the country, so that, as Dacre himself admits, the Eastern Marches were a prey to constant robberies, fire-raisings, and murders. Incensed at this behaviour, Albany resolved that he would no longer show forbearance to this factious and turbulent baron, and having by fair promises induced him and his brother William to visit Holyrood, in September, 1516, he caused them both to be arrested, by the advice of the Council, tried on an accusation of treason, condemned and executed. Their heads were exposed above the Tolbooth and their estates confiscated.

- The Great Historic Families of Scotland

Buchanan mentions that one of the charges brought against the Chamberlain was that he was accessory to the defeat at Flodden and the death of the King, which shows at what an early period this unfounded report was prevalent. The historian adds that the accusation, though strongly expressed, being feebly supported by proof, was withdrawn.

Another brother, David Home, ‘Prior of Coldingham, was shortly after assassinated by the Hepburns. The execution of Lord Home was keenly resented by his vassals and retainers. Among the fierce Border race the exaction of blood for blood was regarded as a sacred duty. Albany himself retired to France and thus escaped their vengeance, but they determined to revenge the death of their chief by slaying the Regent’s friend, the Sieur de la Bastie, a gallant and accomplished French knight, whom he had appointed Warden of the Eastern Marches in the room of Lord Home. For this purpose, David Home of Wedderburn and some other friends of the late noble pretended to lay siege to the tower of Langton, in the Merse of Berwickshire, which belonged to their allies and accomplices, the Cockburns. On receiving intelligence of this outrage, the Warden, who was residing at Dunbar, hastened to the spot accompanied by a slender train (19th September, 1517). He was immediately surrounded and assailed by the Homes, and, perceiving that his life was menaced, he attempted to save himself by flight. His ignorance of the country, however, unfortunately led him into a morass near the town of Dunse, where he was over-taken and cruelly butchered by John and Patrick Home, younger brothers of the laird of Wedderburn. That ferocious chief himself cut off the head of the Warden, knitted it in savage triumph to his saddlebow by its long flowing locks, which are said to be still preserved in the charter-chest of the family, and galloping into Dunse, he affixed the ghastly trophy of his vengeance to the market cross. The Parliament, which assembled at Edinburgh on the 19th of February, 1518, passed sentence of forfeiture against David Home of Wedderburn, his three brothers, and their accomplices in this murder. The Earl of Arran, a member of the Council of Regency, assembled a powerful army and marched towards the Borders for the purpose of enforcing the sentence. The Homes, finding resistance hopeless, submitted to his authority. The keys of Home Castle were delivered to Arran, and the Border towers of Wedderburn and Langton were also surrendered to him. The actual perpetrators of the murder, however, made their escape into England, and it is a striking proof of the

- The Homes

weakness and remissness of the Government at that time that none of them were ever brought to trial or punishment for their foul crime.*

The forfeited title and estates of Lord Home, who left no male issue, were restored, in 1522, to his brother GEORGE, who became fourth Lord. Like his predecessors, he appears to have possessed the fickleness and instability of character which the family probably inherited from their versatile ancestors, the Earls of March. He deserted the party of the Earl of Angus—Queen Margaret’s second husband—whom the Homes had hitherto supported, and became for a time a strenuous partisan of Albany, probably in return for the restitution of the family estates and honours. But two or three years later he was found fighting on the side of Angus at the battle of Melrose, where Sir Walter Scott of Buccleuch made an unsuccessful attempt to rescue the young King, James V., from the hands of the Douglases. Shortly after he assisted the Earl of Argyll in driving Angus across the Border and compelling him to take refuge in England. It is due to Lord Home, however, to state that, though thus inconstant in his adherence to the cause of his brother nobles, the remark which Sir James Melvil made respecting his son is equally applicable to him, that ‘he was so true a Scotsman that he was unwinnable to England to do any thing prejudicial to his country.’ There were very few Scottish nobles of that day of whom this could with truth be said. In August, 1542, Lord Home, along with the Earl of Huntly, defeated, at Haddon-Rig, a few miles to the east of Kelso, a body of three thousand horsemen, who were laying waste

- David Home, the leader in the plot for the murder of De la Bastie, was one of the ‘Seven Spears of Wedderburn,’ who fought at Flodden, where his father and eldest brother were killed. He seems to have been as noted for his ferocity and blood-thirstiness as for his bravery. He was so powerful in the Merse that it was said ‘ none almost pretended to obtaining his leave.’ Blackadder, Prior of Coldingham, however, refused to submit to his arbitrary control and claims; and Home, meeting him one day while he was following the sports of the chase, assassinated him and six of his attendants. His brother, the Dean of Dunblane, shared the same fate. The object which the Homes had in view was to obtain possession of the estate of Blackadder, that had belonged to Andrew Blackadder, who fell at Flodden, leaving a widow and two daughters, at that time mere children. The Homes attacked the castle of Blackadder, where the widow and her daughters resided. The garrison made a brave resistance, but were ultimately obliged to surrender. The widow was compelled to marry Sir David Home, and her two daughters were contracted to his younger brothers, John and Robert (the former one of the murders of De la Bastie), and were closely confined in the castle until they came of age. The estate was entailed in the male line, and should have passed to Sir John Blackadder of Tulliallan, but he was waylaid and assassinated by the Homes in 1526, and they ultimately succeeded in retaining possession of the estate by force.

- The Great Historic Families of Scotland

the country under the command of Sir Robert Bowes, the English Warden, the banished Earl of Angus, and Sir George Douglas. The encounter was fierce and protracted and was decided in favour of the Scots by the timely arrival of Lord Home with four hundred lances. The English were completely defeated, and left six hundred prisoners in the hands of the victors, among whom were the Warden himself, his brother, and other persons of note. A few months later, in conjunction with Huntly and Seton, Home did good service by harassing a formidable army which invaded Scotland under the Duke of Norfolk, and compelling him in little more than a week to retire to Berwick and disband his forces. In a skirmish with the English horsemen, on the 9th of September, 1547, the day before the battle of Pinkie, Lord Home, who commanded the Scottish cavalry, was thrown from his horse and severely injured, and his son, the Master of Home, was taken prisoner. His lordship was carried to the castle of Edinburgh, where he died. His wife, a co-heiress of the old family of the Halyburtons of Dirleton, stoutly defended Home Castle against the Protector Somerset, but was ultimately obliged to surrender, and it was garrisoned by a detachment of English troops. Lord Home left two sons and a daughter.

ALEXANDER, his elder son, fifth Baron, was a true representative of his family both in its strength and its weakness. He was personally brave, and fought with great distinction against the English invaders in the campaign of 1548 and 1549. Unlike a large body of the nobles, he steadfastly supported the independence of the country, and was proof against the bribes and threats of the Protector Somerset and his agents. He recovered Home Castle from the enemy in a very daring manner. A small band of his retainers, who were on the watch for an opportunity of surprising it, perceiving on a certain night that the guards had relaxed their vigilance, boldly scaled the precipitous rock on which the fortress was built, and, killing the sentinel, obtained possession of the castle without difficulty. Fast Castle, another fortalice of the family, was retaken in a manner equally adventurous. A number of armed men concealed themselves in the waggons which were bringing a supply of provisions for the garrison. Suddenly starting out of their hiding-place, the Scots seized the castle gates and admitted a strong body of their countrymen, who were waiting their signal in the immediate vicinity of the fort. The garrison being taken unawares, were easily

- The Homes

overpowered, and the place secured. Lord Home was appointed to the office of Warden of the Eastern Marches, so often held by his ancestors, and was one of the commissioners who negotiated the treaty between England and Scotland at Norham in 1559. He supported the Reformation, and sat in the Parliament which abolished Popery and established the Protestant Church in 1560; but in 1565 he attached himself to the party of Mary and Darnley, who in the following year, with a splendid retinue, visited the family castles of Home, Wedderburn, and Langton. He seemed to stand so high in the favour of the Queen at this time that it was expected that the ancient title of Earl of March would be revived in his favour. He was one of the nobles who signed the discreditable bond in favour of the Queen’s marriage to Bothwell, but only a few weeks later he joined the association for the defence of the infant King, her son, and along with the Earls of Morton, Mar, Glencairn, and Athole, Lords Lindsay, Ruthven, Graham, and Ochiltree, he subscribed the order for Mary’s imprisonment in Lochleven Castle. After the Queen’s escape from that fortalice, Home brought a body of six hundred spearmen to the assistance of the Regent Moray at the battle of Langside, where he was wounded both in the face and the leg; but the fierce charge of the Border spearmen contributed not a little to the defeat of the Queen’s army. In 1569, however, he once more changed sides, and joined Queen Mary’s party. He assisted Kirkaldy of Grange and Maitland of Lethington in holding out the castle of Edinburgh to the last against Regent Morton; but on its surrender in May, 1573, he was more fortunate than his associates, for though he was brought to trial before the Parliament and convicted of treason, he was pardoned, and obtained the restoration of his estates. He died 11th August, 1575.

ALEXANDER, sixth Lord Home, stood high in the favour of King James VI., by whom he was created Earl of Home and Baron Dunglass, 4th March, 1605.

In the Parliament held in 1578 Lord Home obtained the reversal of the forfeiture passed against his father for his adherence to the party of Queen Mary. David Home of Godscroft represents this as having been mainly brought about by the intervention of his brother, Sir George Home of Wedderburn, with the Earl of Morton; and, according to Godscroft, it was against the will and judgment of the Regent that Wedderburn’s mediation was effectual. The affair

- The Great Historic Families of Scotland

affords a striking illustration of the influence of the feeling of clan-ship and fidelity to the chief overpowering even the dictates of self-interest. Morton frankly informed Sir George Home that ‘he thought it not his best course.’ ‘.For,’ he said, ‘you will never get any good out of that house, and if it were once taken out of the way you are next; and it may be you will get small thanks for your pains.’ Sir George answered that ‘the Lord Home was his chief, and he could not see his house ruined. If they were unkind, that would be their own fault. This he thought himself bound to do. And for his own part, whatsoever their carriage were to him, he would do his duty to them. If his chief should turn him out at the fore-door, he would come in again at the back-door.’ ‘Well,’ said Morton, ‘if you be so minded it shall be so. I can do no more but tell you my opinion.’ And so he consented.*

The Earl appears, however, to have been largely imbued with the ferocity of the Borderers. It is mentioned by Patrick Anderson that in May, 1593, ‘Lord Home came to Lauder, and asked for William Lauder, bailie of that burgh, commonly called William at the West Port, being the man who hurt John Cranston (nicknamed John with the Gilt Sword). Lauder fled to the Tolbooth, as being the strongest and surest house for his relief; but the Lord Home caused put fire to the house, and burnt it all. The gentleman remained therein till the roof-tree fell. In the end he came desperately out amongst them, and hazarded a shot of a pistol at John Cranston, and hurt him; but it being impossible to escape with life, they most cruelly, without mercy, hacked him with swords and whingers all in pieces.’